Ravens and the dark side of nature

He was perched on a wooden fence post, croaking “Tok, Tok” repeatedly and seemingly to himself. From across the road, I could see his beak opening and his crown feathers flaring with excitement. He was looking at the ground, with one set of claws on a wire and the other on the post, and there was something in the yellow grass that held his attention. Though I couldn’t see what it was, I knew it was more than likely dead or dying.

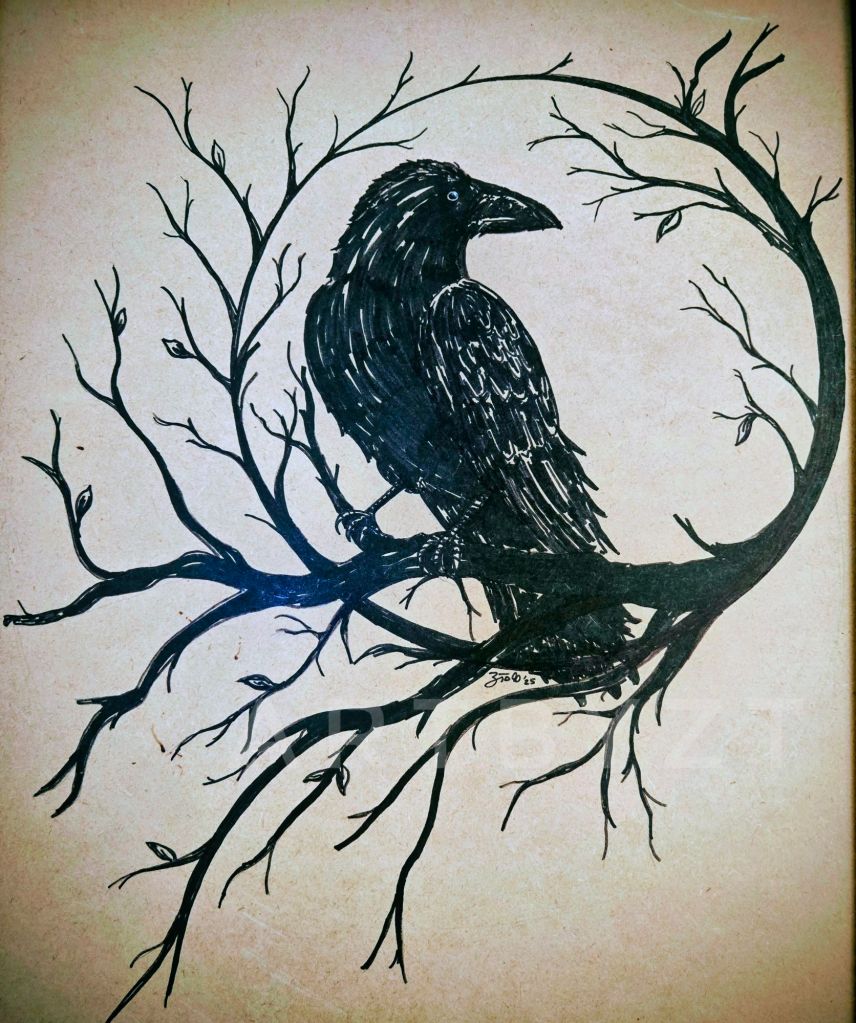

Maybe this assumption came because it was October and spooky things were already on my mind. But it was more than just that. This was a raven after all, a bird who makes a living on death. I’ve spotted many of them over the years, but never with such stark contrast, set against the classic desert panorama–a landscape bathed in sunlight, full of browns and reds, distant plateaus overlaid by brilliant blue sky. The raven here seemed superimposed, like a black hole in the galaxy or a gash in a painting. He was a visual assertion that despite an abundance of warmth and light, the desert holds space for darkness.

Of course ravens are rarely just fixtures on the scenery. Always up to something, they can be brash and loud, like rocks thrown into a pond. Usually, when their attention is captured, it means some opportunity or advantage is about to be gained. I’ve never seen them as casual observers, but usually on some task, either scavenging roadside or making murderous forays into the trees, with desperate little birds hot on their tail feathers.

One day I saw a large raven steal a house sparrow chick from its nest at the top of a telephone pole. The chick’s parents were dive-bombing desperately at the raven’s head, but were finally forced to quit after the baby was pulled apart and devoured right in front of them. Adding to the savagery was the raven’s nonchalance, like a teenager eating a Big Mac.

This neighborhood bully image is supported by the raven’s size. I’m not sure if many people understand how big they really are, at least as big as a chicken, if not bigger. Ravens are similar in appearance to crows, but larger, and their beaks are more powerful and shades darker. They have feathers that are not just black, but jet black, with a bluish tint that can only be seen when the bird turns at certain angles in the sunlight. This glare creates a metallic, even spectral appearance.

Still, the raven is not just a plunderer, scavenger, murderer. Anthropomorphism aside, he is also intelligent, which adds another level of intrigue. When you observe a raven, he’s also observing and judging you. Scientists have said that ravens have the intelligence of a two or three year old child, and there is even documentation of ravens using tools (mostly sticks and rocks) to obtain food and water, which is unparalleled in the avian world. When it comes to vocalization, only parrots can outperform the raven.

With all this, it’s easy to see why ravens have long been part of Halloween decorations, horror movies, scary stories and the darker side of folklore. The famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe depicts, in a masterful way, the perception of trickery and the feelings of dread that are possible when encountering the raven. Such moments can feel more like interactions as opposed to just mere “sightings.”

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,”Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “are sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore–Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!” Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

One such experience took place when I was a child sometime in the mid 1980’s. I was on top of a houseboat on Lake Powell in Southern Utah. It was early morning, and the water in the high-walled cove where we had anchored was dark and still. The sky was just beginning to brighten, and we awoke to the smell of breakfast cooking on the lower deck. The owner of the boat, a friend of my father, had been coming up the stairs and back down, cleaning and organizing the boat. Suddenly we heard two ravens talking to each other on the cliffs above, with deep, gravely, voices that echoed across the canyon making them seem even more supernatural.

One little boy, still inside his sleeping bag, became quiet and began to stare into the sky. He was the boat owner’s son, and after a moment he couldn’t help but ask: “What are they saying Dad?” The innocence of the question was indelible.

“They’re saying, ‘Eat Johnny,” the father replied, with a mischievous smile. We all giggled, but little Johnny remained silent, his eyes fixed upward, his body frozen with fear. It was only later in life when I realized that “Eat Johnny,” was entirely within the realm of possibilites.

Edward Abbey depicted the raven’s adaptability as one of nature’s undertakers. In “The Dead Man at Grandview Point,” he described them rising “heavily and awkwardly” from the bloated corpse of a man who had fallen victim to the wilderness.

Despite my many observations, I had never actually handled a raven until just a few years ago. My kids had barged into the house one day, wide-eyed, to tell me there was a large bird in the garage. I went out and found a raven on the floor. She appeared to be an older bird, thinning, but still with vitality in her eyes. I couldn’t immediately tell if she had any injuries, but she’d obviously had her bell rung, probably from hitting a window, or the side of the house. She must have come in through the open garage door. I put on a pair of gloves and corralled her in a corner, scooping her up and holding her wings close to her body so she wouldn’t thrash. Then I took her out to the driveway, with open sky above us, and set her on the ground to see what she would do.

She looked at me for a moment, with those dark but shiny eyes that seemed to be sizing me up and drawing me in. Then, in an instant, she took off, lifting upward with big flapping wings toward a stand of nearby trees. Soon she had disappeared into a tangle of dead limbs and shadows. Never once did she look back to thank me. There was only a sense that she had made yet another escape and seized yet another opportunity.