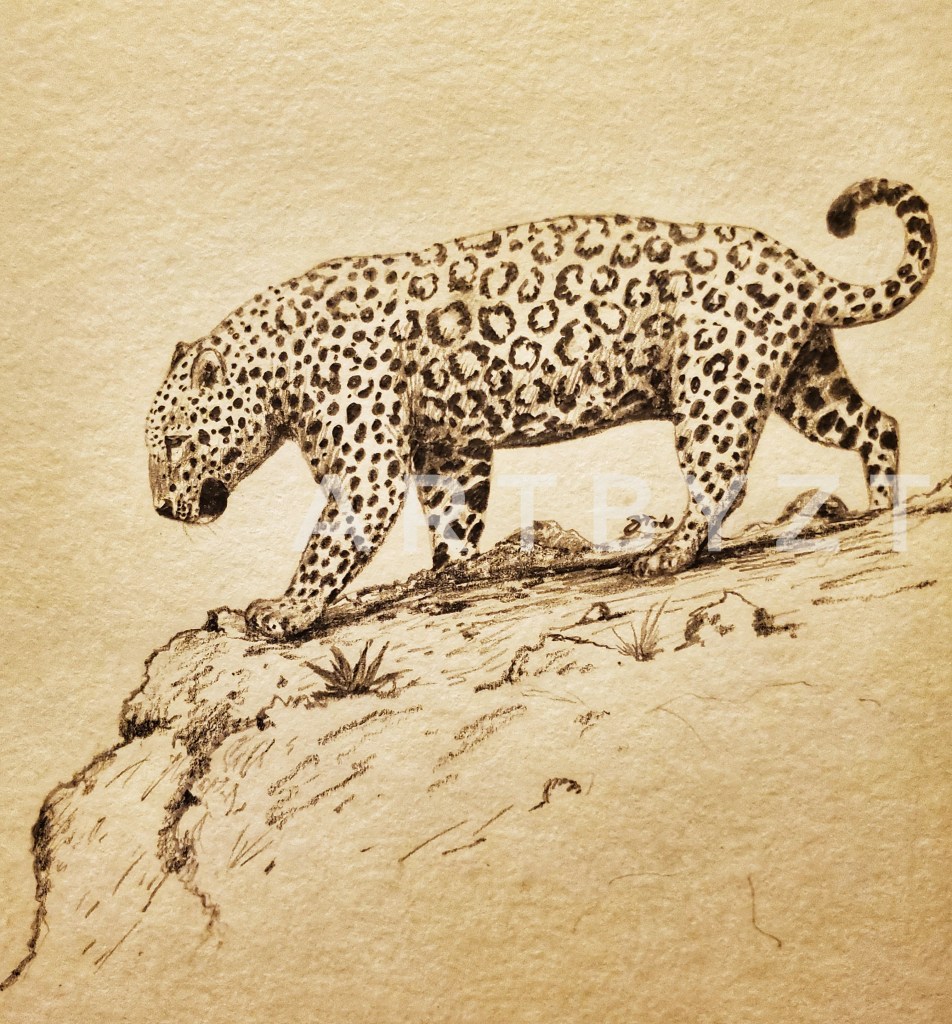

Masters of terrain, they enliven the desert like no other animal can

On a bright summer morning, near the 4th of July, I was navigating foxtails and prickly pear cactus, making my way toward an outdoor amphitheater in a small community park in Southeastern Utah.

The heat was tolerable, partly thanks to a nearby canyon which still had shade, a small creek, and a latent pool of overnight air. After about 500 feet of meandering, the dirt path soon diffused across several big slabs of sandstone, speckled with patches of green and orange lichens.

Perhaps it was luck, or just that my eyes were already primed for color, but I happened to notice something especially vivid and alive, some 30 feet away. Whatever it was, it was perched near the back row of the amphitheater.

As I moved closer, I began to see the big collared lizard, warming himself in the sun.

For a moment he watched me as I stood watching him. He seemed very self-assured, but as soon as he realized my presence he was gone in a blur, disappearing into a nearby crevice. It was as good a find as any reptile enthusiast could ask for. I was struck, perhaps more than ever, by the vibrancy of his markings that, in isolation, seemed more tropical than temperate.

I’ve had many such encounters with wild lizards over the years. It’s true that sometimes they can seem ubiquitous, commonplace or even pesky, but their prominence on the landscape has made them fine subjects for art and literature and historical accounts of all kinds.

John Muir, while following sheep through the Sierra, made sure to include lizards in his warm and detailed observations:

“Lizards of every temper, style, and color dwell here, seemingly as happy and companionable as the birds and squirrels…”

Edward Abbey, too, seemed to find lizards philosophically useful, and as much a part of the wilderness as the rocks and sunshine:

“The lizard sunning itself on a stone would no doubt tell us that time, space, sun, and earth exist to serve the lizard’s interests; the lizard too, must see the world as perfectly comprehensible, reducible to a rational formula. Relative to the context, the lizard’s metaphysical system seems as complete as Einstein’s.”

As for Muir’s depiction of lizards as being “companionable,” I would say this is true, at least in my experience with Western species. Even the dreaded Gila Monster is mostly a gentleman, unless provoked. (Disclaimer: Do not attempt to prove this.)

In younger days, lizard catching was a regular part of my outdoor adventures. But it was a real challenge to actually get them in your hands. Most lizards seem to have speed woven into their DNA, and the hotter it gets, the faster they become.

Still, when captured, lizards usually relax dramatically, and only occasionally will they attempt to bite, and then for just a moment or two. Releasing a lizard back into the wild is easy, and sometimes they will even pause to say goodbye before jetting off.

As for hunting techniques, I started out catching lizards like a caveman would, using just my hands or maybe my hat. But after more failures than victories, I eventually learned to use tools, including butterfly nets and fishing poles with the line tied into little slip knots at the end. Bucket traps were an option too, but riskier and probably illegal.

Not all of it was fun and games, however. After several solid captures, I realized that many lizards detach all or part of their tails while trying to escape. And there was something about seeing an amputated lizard tail, bloodied and wriggling on the ground, that made the pastime seem less appealing.

These days, I mostly just capture photographs if possible. Lizards are very keen about spotting any movement, being always wary of predators, so it’s easier to get close to them if you move very slowly.

One of the hardest species to photograph are the whiptails, because they, in particular, are full of speed, and their movements are almost bionic. They rarely hold any position for long. Despite this, they’re probably my favorite desert lizard, because they look so much like bigger monitor lizards–or even miniature Komodo Dragons. In reality, whiptails are actually more closely related to the Tegu, a large lizard native to South America.

Whiptails occupy riparian areas, where willow, rabbitbrush and tamarisk are common. They are also the kings of dry riverbeds and trailside clumps of Gambel’s oak and Manzanita. Their presence can often be detected by their distinctive tracks in the sand, which consist of long continuous lines flanked by tiny claw marks.

As for the species at higher elevations (mostly the fence lizards) they can be more muted in color and athleticism, but they are respectable nonetheless. They can often be spotted on the tops of boulders, doing little push-ups as a type of signal to other lizards or even intruders.

One of the most amazing of the desert dwelling lizards is the Chuckwalla. It’s a species that was often considered food for native peoples in the Southwest. Chuckwallas are known for their ability to inflate their bodies inside rock cavities, wedging themselves inside and making it nearly impossible for a predator to remove them.

With all the charming, and sometimes bizarre, antics that lizards can display, it’s easy to agree they deserve recognition. And this week, August 14th, is World Lizard Day, so it just made sense to write something about them. Ultimately, lizards are so admirable because they seem unwilling to go unnoticed, especially when compared to other reptiles, like bashful snakes.

As for the collared lizard, he certainly seemed to think he was something special that day. And how could he not when his territory included an amphitheater of all things? In retrospect, it was a perfectly poetic setting–the best of backdrops for one of nature’s true performers.