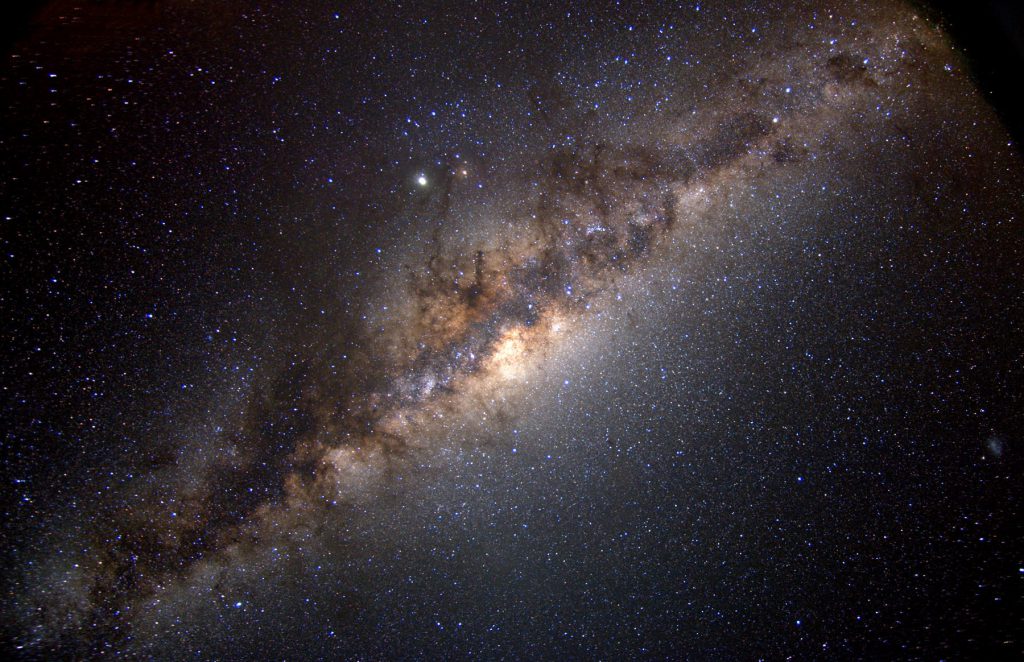

The stars never shined so bright as they did on that summer night more than 30 years ago. Lying on my back in a sleeping bag, on the sandstone and without a tent, I stared up into a vast black sea, with floating diamonds, and for the first time felt hopelessly small in the universe and yet somehow still important.

I was exhausted but couldn’t let myself fall asleep just yet–not with The Milky Way, Orion’s Belt, Ursa Major, the Big Dipper, hovering over me like an open book.

While never much of an astronomer, I could still appreciate a sky without light pollution, especially compared to the washed out skies I knew from the big city. I had learned about the constellations during field trips to Hansen Planetarium in Salt Lake. But that dark, domed theater, made for city-slickers, was just a figment compared to the view of the galaxy before me now–layer upon layer in 3D.

Our Boy Scout troop had stopped here as part of a week-long trip to the San Rafael Swell in Southeastern Utah. For dinner we had chili and salad, significant because, like the night sky, it was the first time I had truly appreciated vegetables. It wasn’t easy for a teenage boy to admit, but that crisp lettuce, straight out of the cooler, was the remedy to a long day of parched travel.

We’d been riding in a white Ford passenger van, pulling a trailer of float-tubes, mountain-bikes, Cheetos and sodas for about two days. The van looked similar to the one neighborhood moms had warned us about back home–always driven by some scraggly, bearded man looking to lure kids with candy and then whisk them away forever. But the stranger probably would’ve jumped out of this van at highway speeds, because it was already overloaded with loud and dusty boys, tweaked out on sugar.

Looking back, I marvel at the planning and logistics that must’ve gone into this trip. The real ones driving the van–those beleaguered scout leaders–had done a lot of thinking. They were just part-time adventurers, willing to leave desk jobs in the city to take unruly boys into potential danger. They’d have to endure terrible scrutiny these days to even try it. Maybe rightly so.

Of course none of it could’ve been considered “high adventure,” but such travel shouldn’t be underestimated. Although I was young and naive, I questioned the trip myself. Was there a plan to keep gas in the van when service stations were so few and far between? Was there a medical plan? Did we have enough water? And, probably the most important question, did anyone really know where we were going out in this vast and fiery place?

One of the leaders had experience traveling the area–something about riding around in a Jeep with his father, a geologist for the Bureau of Land Management. I took comfort in this, but also considered how badly the rest of us would suffer without him. What if he fell off a cliff or was taken by a rattlesnake? No one had phones back then. We could be stranded for days before someone found us. In some ways I feared it. In other ways I hoped for it…

The dirt road was part of a web of backcountry trails in Southeastern Utah, some of the most remote wilderness in the U.S, located near Capitol Reef National Park. Dusty and washboarded, it had taken us parallel with the Swell and, if I can recall, toward the town of Hanksville.

At one point we passed near the Muddy River, more of a creek actually, which meandered through a respectable pattern of hidden grottos and alluring canyons. We’d spent the afternoon float-tubing here, at times walking on our hands while our legs trailed behind.

I remember the water was cold (from June runoff) and sand went everywhere–up our shorts, between our toes and into our ears and hair. We’d spent more time in the water than was probably smart, only crawling out when it seemed we were just short of hypothermia.

Once out of the creek, however, we found sun-soaked boulders along the bank. Lying on these, shivering and wet, it was possible to experience one of the greatest warming sensations known to man, enough to make us envy the lizards we’d sent scattering to get there.

After drying off as much as possible, we were back on the road, singing songs, eating junk food and telling stories and jokes until we grew hoarse. Sometimes we were forced back out of the van and compelled to ride our bikes ahead of it. Something had been said among the adults about us needing fresh air and a “more direct experience with nature.”

We complained, of course. But any sense of punishment quickly vanished. While riding our bikes, out from behind van windows, the spectacular views came to life.

All along the plateau we could see the Swell–that long spine of cream-colored rock, rising up like a dragon from a desert ocean. At times there were small groups of pronghorn antelope in the foreground, grazing on patches of grass between sagebrush. Next to the road, we saw globemallow and sego lily and could hear the calls of meadowlarks nearby. All of this was hard to capture in memory. Yet one thing was certain: the Swell had caused my heart for the wilderness to swell.

Being the remnant of a giant rock dome some 75 miles long and 40 miles wide, the bulk of the Swell was formed by tremendous geologic pressure. This upturned sandstone was then subjected to the subtle carvings of wind and water for millions of years.

Because the region is more inaccessible than many of the national parks in Utah, the scenery is not just uniquely carved, but carries with it a real sense of solitude and distance. Some of these wilderness areas are now more protected than they were back then, a contentious issue at times, but the reality of a world that is increasingly overrun.

In 2019, Congress designated the San Rafael Swell Recreation Area (approximately 217,000 acres), as part of the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act. According to the BLM, the region features “magnificent badlands of brightly colored and wildly eroded sandstone formations, deep canyons, and giant plates of stone tilted upright through massive geological upheaval.” (Bureau of Land Management, San Rafael Swell Recreation Area https://www.blm.gov/utso/grd/san-rafael-swell-rec-area )

A few miles southeast of the Swell is a valley of hoodoos, called “goblins” because of the creature-like shapes they take under changing light. It was here in Goblin Valley that we spent one of the last nights of the trip.

After dinner, we played a game of “steal the flag.” What could be wrong with eight boys turned loose into a labyrinth, guided only by the moon–to run through, climb over, fall from or even be crushed by boulders? Despite the risks, this daring permission kept us running and hiding until well after sundown.

When “quiet time” arrived in the park, we took a head count and then staggered and giggled our way back to camp–an open slab overlooking the valley. From this moonlit viewpoint, I could see just how many goblins lived here, clustered together in a mass of gnarled stone like a geological mosh pit.

Now that the party had died down, the stillness that descended was heavy and sublime. Wearily, we unrolled our sleeping bags. I was puzzled at first, maybe even troubled, to see that we didn’t have tents; I’d never slept out in the open before. What about snakes, spiders, scorpions…thunderstorms?

Too tired to care for long, I unzipped the sleeping bag and wedged myself inside. Thankfully I rolled onto my back before finally closing my eyes. And there it was, the night sky that would eventually send me into sleep and into dreams that could be no more vivid than all I had already seen.